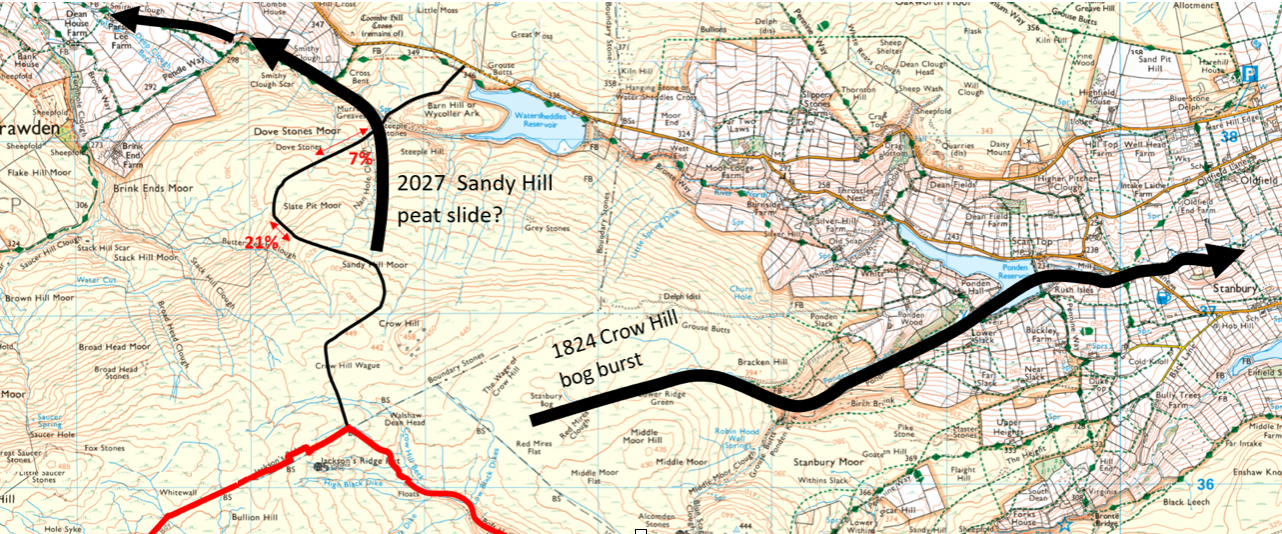

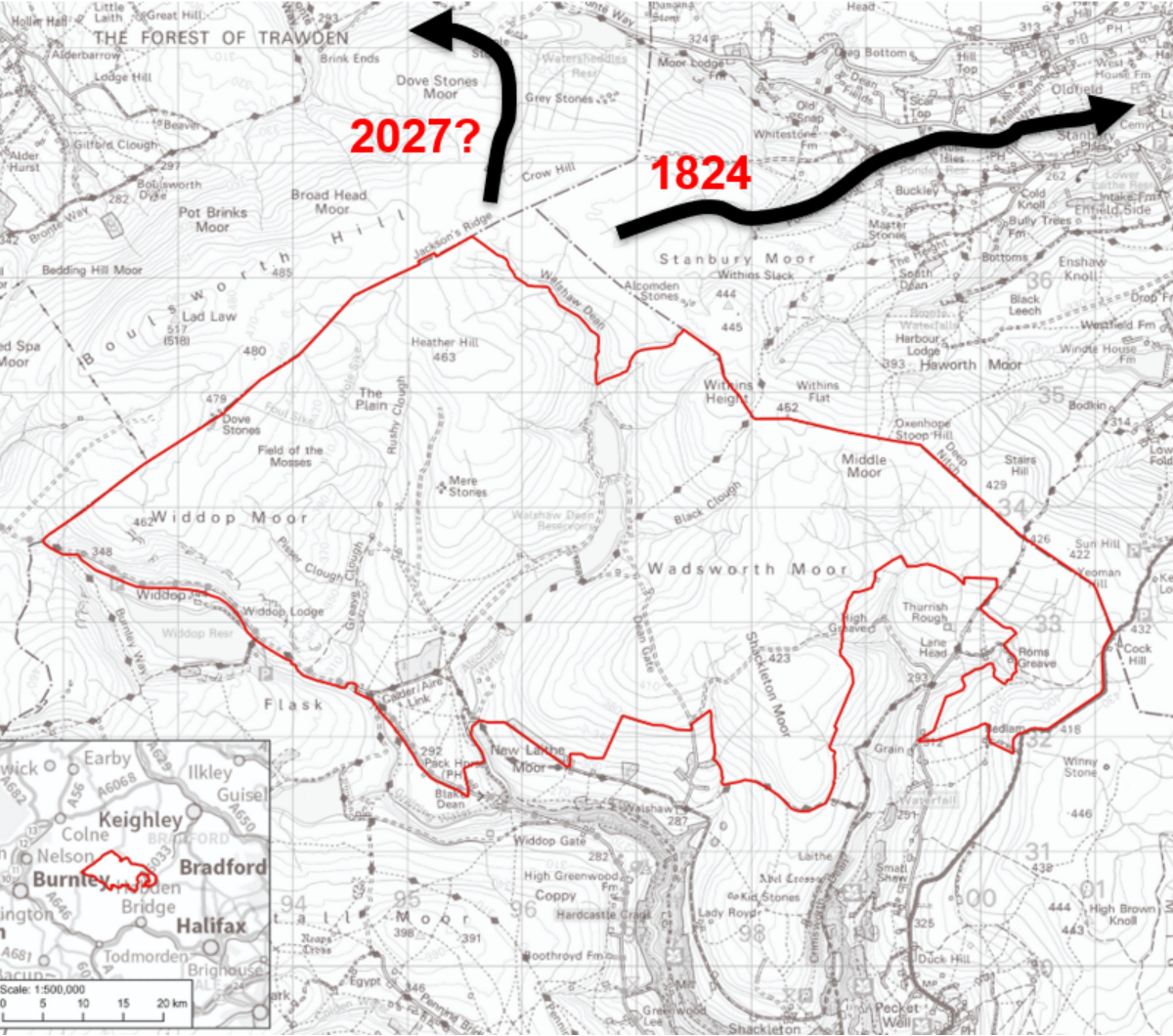

Will Calderdale Energy Park cause a repeat of the 1824 Bog Burst?

Looking across to Watersheddles Reservoir, from the edge of Middle Moor Flat over the possible route of the 1824 mudslide. Photo John Page

The torrent was up to five metres deep and large boulders were picked up and hurled through the air. The devastation can still be seen on the cratered moors today. For weeks afterwards, the Worth was full of dead fish. Ann Dinsdale, Principal Curator at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, narrates a short film of the event.

This huge boulder was carried here in the bog burst. Photo: John Page

The following year in 1825 The Edinburgh Journal of Science published an academic article by David Brewster : Notice of the Rare Atmospheric Phenomenon 1824 in which reference is made to the bog burst.

“Reports from Kelso, Berwick, Belford, Newcastle, and many places in Yorkshire and Northumberland, give accounts of a most alarming storm of thunder and lightning having occurred, accompanied with a’ vast quantity of rain, and spreading destruction over a great extent of the country.—Many men and domestic animals were killed by the lightning. It was during this storm that the subterraneous bog burst at Keighley in Yorkshire, which may be traced to the vast torrents of rain that seem to have accompanied the contemporaneous storm.”

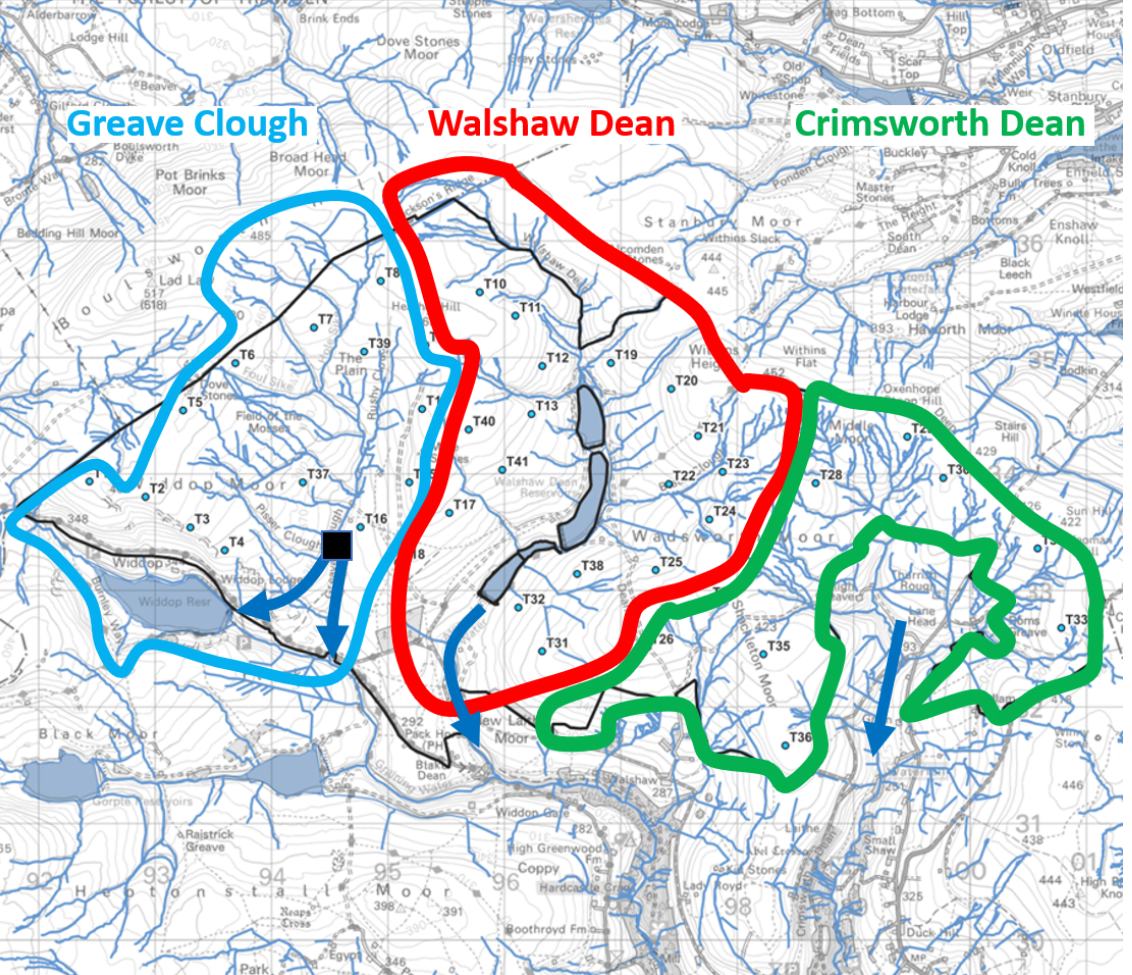

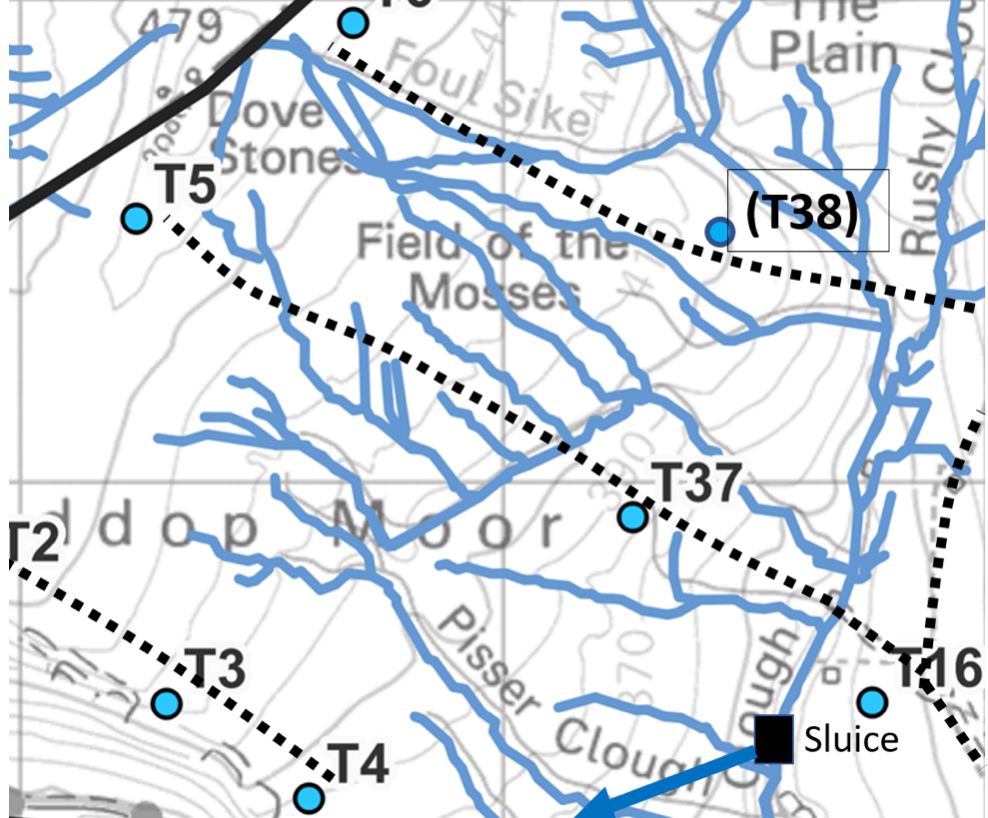

Prior to the bog burst a period of high temperatures and dry conditions were followed by several days of exceptionally heavy rain. This would have led to a very large build-up of water in a dry Stanbury Bog, creating extremely unstable conditions in the deep peat overlaying the sedimentary bedrock. A slippery shear plane formed between the contrasting peat and sandstone, causing the the deep peat to slide down the convex slope. The mudslide would flow north-easterly under gravity into the steep sided valley of the Ponden Clough Beck. Fortunately there was no reservoir in 1824, for the force of the bog burst would have destroyed the dam, adding the reservoir’s water to a murderous torrent heading for Haworth.

Bog bursts are not uncommon. A lot of academic research has been done in recent years on them, and they are often caused by wind farm construction. The Irish Peatland Conservation Council wrote this:

“Bog bursts” or peat flows are a dramatic form of peat erosion. Sections of peat on sloped areas can break off from the main body of a blanket bog and flow down-slope, similar to a volcanic lava flow. Bog bursts usually happen after heavy rain on sites which have been put under human pressures, such as overgrazing, turf cutting or wind farm construction. For example, the construction of a wind farm at Derry Brien, county Galway resulted in a large bog burst causing almost half a square km of blanket bog to travel 2.5 km (Lindsay and Bragg, 2005). During a bog burst it is thought that the living plant layer of the bog tears due to stress and the very wet peat centre flows under the influence of gravity. Other bog bursts have been recorded in Ben Gorm in Connemara, on Clare Island in Co. Mayo and 52 separate bog bursts were recorded at Pollatomish, Co. Mayo”.

Film was taken of a small peat slide on relatively flat ground, caused by construction of Viking WF on Shetland.

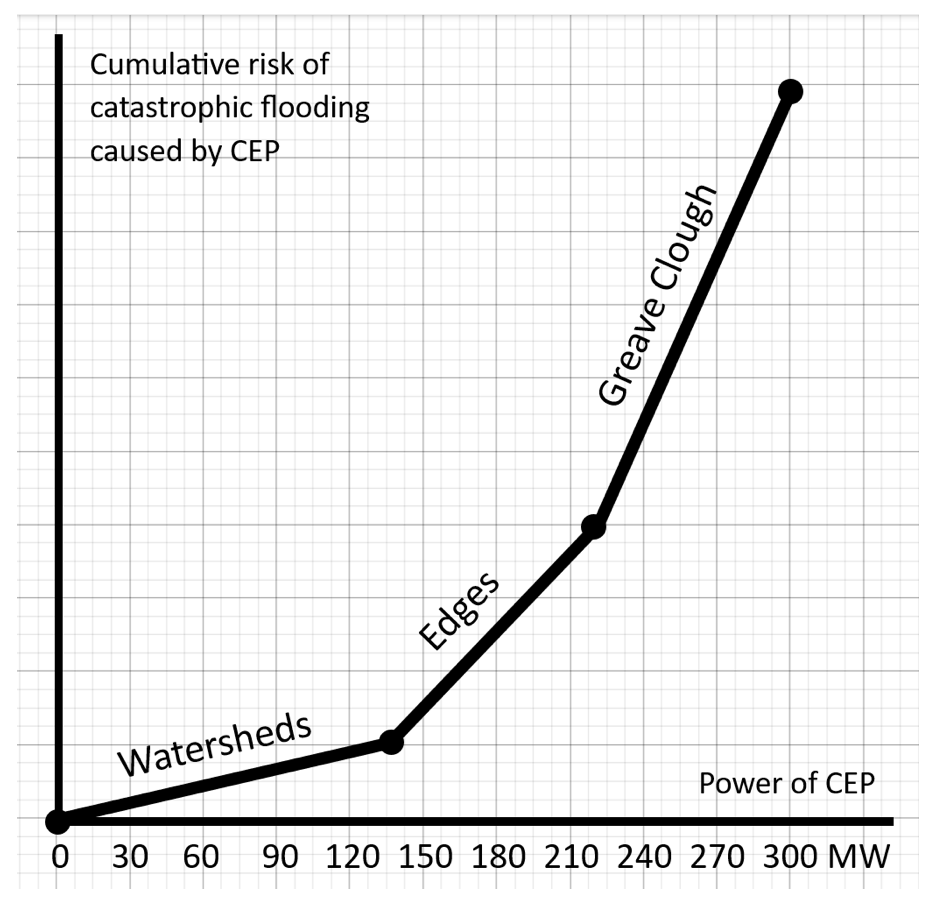

Given that CWF Ltd presented such an unfinished proposal at their public consultation, we can have no confidence at all that any thought has gone into the potential for catastrophic peat slides on the north side of CEP.